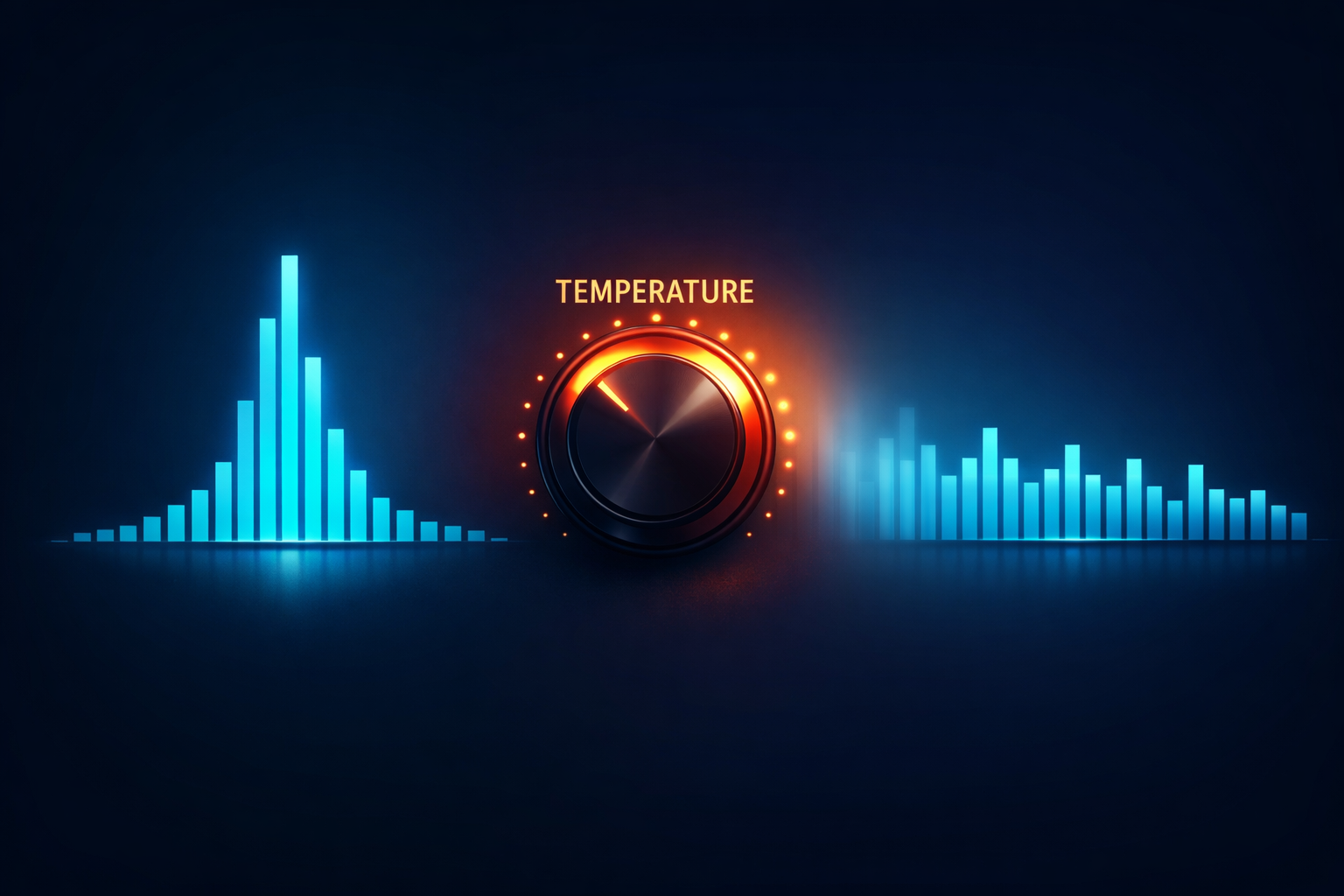

Every API call to ChatGPT , Claude , or any other LLM includes two parameters most people either ignore or tweak randomly: temperature and top-p. The defaults work fine for casual use, so why bother understanding them? Because these two numbers fundamentally control how your model thinks.

The temperature value determines whether the model plays it safe or takes creative risks while the top-p value decides how many options the model even considers. Together, these values shape the personality of every response you receive.

I’ve watched developers cargo-cult settings from others without understanding what they do. “Set temperature to 0.7 for creative writing” becomes tribal knowledge, passed down without explanation. Let’s fix that by opening the hood and examining the mathematics that makes these knobs work.

“Temperature doesn’t make the model smarter or dumber. It changes how much the model trusts its own first instinct.”